Imaging scientists at NYU Langone Health and its Center for Advanced Imaging Innovation and Research have developed two new techniques to obtain sharper images from noisy scans at low-field MRI. In two articles published recently in the journal Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, the researchers describe the new methods and conclude that the advances offer “a promising approach for improving image quality and scan efficiency in low-field MRI” and “hold great potential for broad use” across applications. The applications they have in mind are an entirely new kind of imaging.

While medical MRI scanners today operate at high field (typically 1.5 or 3 tesla), low-field scanners, most of which are currently run by research centers, work at fields of about 0.5 tesla and lower. The possibility of imaging at comparatively weaker fields has been gathering interest because weaker magnets are cheaper to produce, ship, install, and operate; they carry the promise of lower costs and broader access. However, lower magnetic field also means less signal relative to noise.

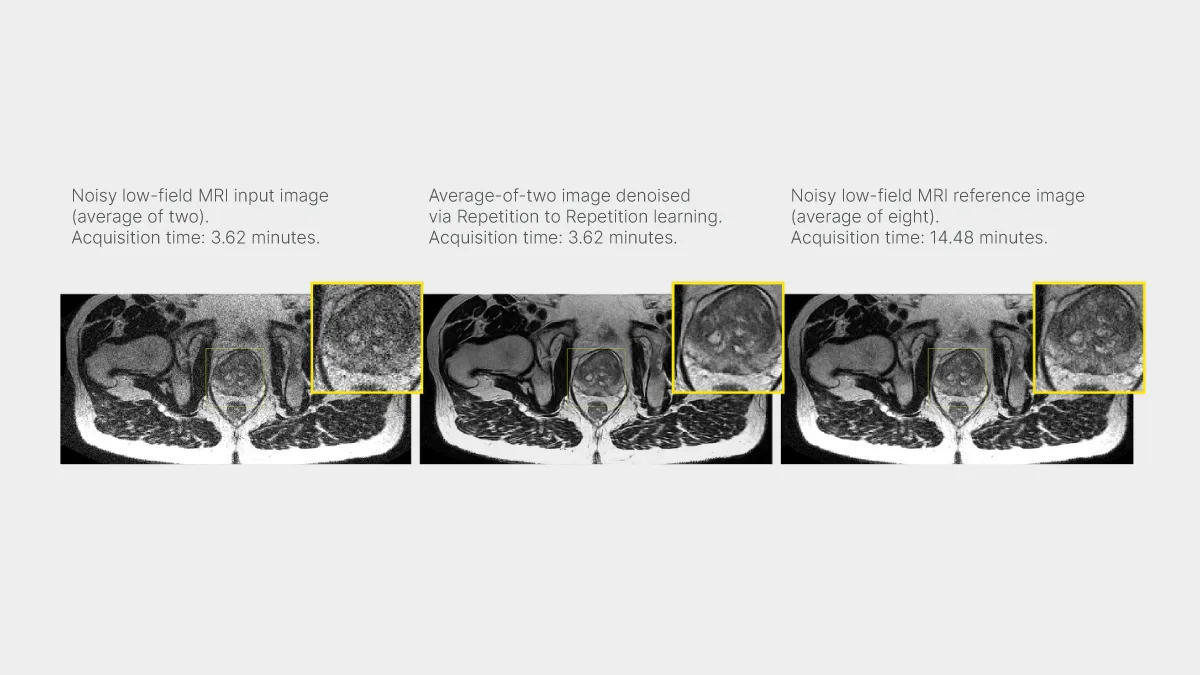

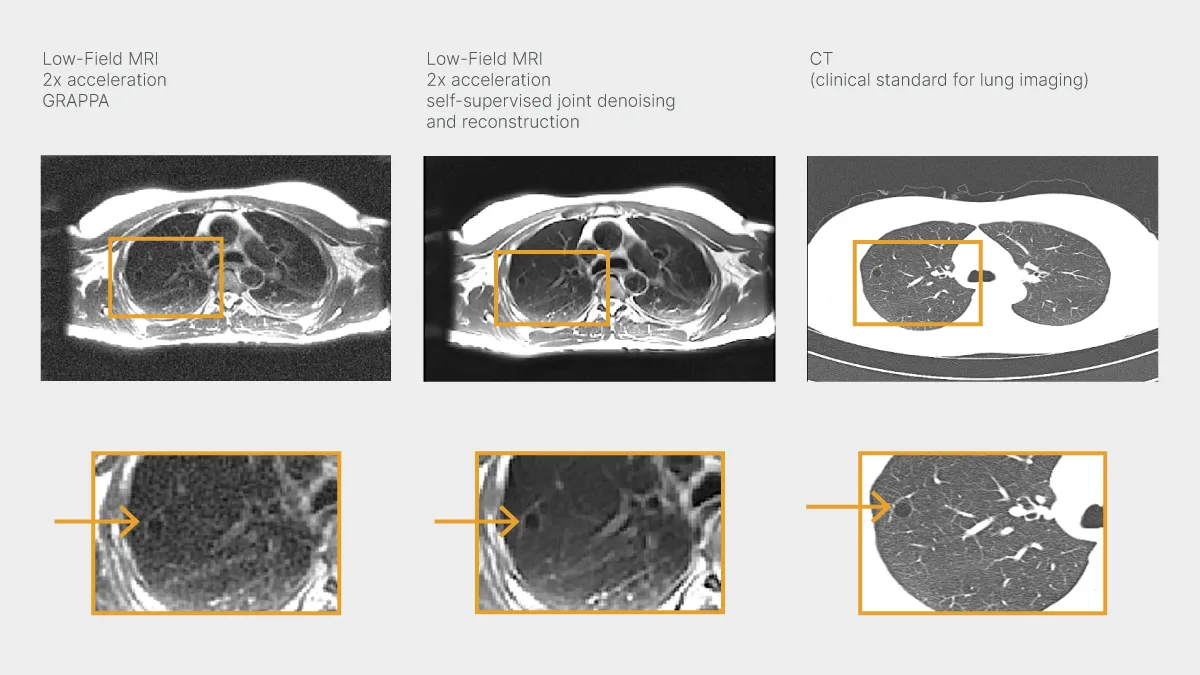

In the studies—one led by Nikola Janjušević, PhD, the other by Jingjia Chen, PhD, postdoctoral fellows at NYU Grossman School of Medicine—the authors demonstrate the new approaches on low-field MRI of the brain, prostate, and lung. In each case, the principal technical advance lies in reducing the signal penalty that forces impractically long scan times at low field.

“At 3T it takes about three, four minutes to get beautiful images of the prostate,” said Li Feng, PhD, associate professor of radiology at NYU Langone and senior author of both studies. He estimated that getting to similar quality at 0.55 tesla would require an approximately half-hour scan.

But although Dr. Feng and colleagues are aiming to match the speed of high-field MRI, they are not looking to rival clinical images. “The point is not about whether the quality is comparable,” Dr. Feng said. “It’s about information. The idea is to monitor longitudinally rather than image to diagnose or screen.”

Welcome to radiology as a tool of preventive medicine: instead of reserving imaging for the unwell who present with symptoms, monitor the healthy for presymptomatic changes.

In this vision, an initial clinical-grade MRI is combined with medical history, labs, and other health information to form a rich baseline of a person’s health, then followed by periodic scans to monitor status while AI mines the data for earliest signs of trouble.

A vocal proponent of this idea is Daniel Sodickson, MD, PhD, NYU Langone’s former chief of innovation in radiology and the founding investigator of the Center for Advanced Imaging Innovation and Research. In a recent book, The Future of Seeing, Dr. Sodickson, who is now chief medical officer at Function Health, imagines a world where a “latticework” of imaging and sensing devices embedded in wearables, clothing, furniture, and the built environment traces a near-constant trendline of our health.

Early nodes of this latticework are emerging as health-tech devices and preventive MRI scans. But longitudinal health tracking won’t make it to the mainstream without scanners that are far more affordable than those on today’s medical device market.

“That’s why we started on this project,” said Dr. Feng, to take steps toward this futurescape by looking to its nearest plausible landmark: low-field MRI.

Turning Noise Against Noise

In every MRI exam, noise rides alongside signal. Their relative proportion, known as signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), determines the fidelity of acquired data and the quality of reconstructed images.

At low field, MRI does not create strong enough polarization in nuclear spins to reap high signal, explained Dr. Chen, lead author of one of the new methods. “We can definitely see anatomical structures, but they’re buried in snowflakes of noise,” she said. And seeing better through that snow currently requires scanning longer.

To counter this, the research team has focused on the very characteristic that makes noise such a nuisance: its randomness.

“Noise cannot be learned,” said Dr. Chen. But signal can. That’s the essence of the principle known as Noise2Noise, which lies at the core of the new techniques.

Using bespoke MRI acquisition strategies and deep learning methods, the scientists trained artificial intelligence models to predict the structure of images based on subsets of low-field MRI data (in other words, based on data from shorter scans). In the study led by Dr. Janjušević, a once-repeated low-field acquisition created a pair of images, then a network trained on the first image to learn the second. In the study led by Dr. Chen, raw MRI data from a low-field acquisition were “split,” and a network learned to predict a fully sampled image from one of the splits.

Because the acquisition pairs and the acquisition splits corresponded to nearly identical ground truth, their signal shared a good deal of structure. But noise, due to its unpredictable nature, differed randomly between both the pair members and the data splits. This twinning of underlying structure without a twinning of noise has allowed the network in each study to learn to predict fully sampled images from noisy, undersampled data.

In a sense, each process creates more noise the better to subdue it. The network learns to look past the randomness while focusing on order. “We let the noise reveal itself,” said Dr. Chen.

The researchers named one of the methods self-supervised noise-adaptive MRI denoising via repetition to repetition (Rep2Rep); the other, self-supervised joint reconstruction and denoising of T2-weighted PROPELLER MRI. Each name hints at the method’s main technical features.

Self-supervision liberates the machine learning models from having to train on high-quality, fully-sampled reference images—a major bottleneck at low field, where such images are hard to acquire in the first place.

Noise adaptivity refers to a model’s ability to generalize across various levels of noise via noise estimation provided to the network. Dr. Feng explained that noise-adaptivity allows the model to handle discrepancies between train and test data, making the approach more flexible. “We can use high-field data for training and apply it to low-field data, which is a big advantage,” he said.

Supervised joint reconstruction and denoising refers to cleaning up an image while assembling it—in contrast to the conventional approaches in which denoising is done before or after image reconstruction.

Reducing noise is a tricky task, rife with pitfalls on either side of image formation. Traditionally, denoising has been performed after reconstruction, but in recent years a trend toward denoising raw data has emerged. This strategy is rooted in the realization that isolating true signal closer to the source gives that signal more room to drive the steps that follow, bringing more efficiency to the chain of transformations each of which stands to propagate and amplify noise (and thus to make the task of denoising post-reconstruction more complex). A semantic caveat is that reconstruction algorithms often exert a denoising effect to varying extents by virtue of enforcing regularization terms or drawing on structural priors. Dr. Chen said the new technique she has led differs from these approaches.

She likened the new process to pursuing two mutually beneficial attention strategies: focusing on self-consistency (the signal) while looking away from randomness (the noise). “It increases the fidelity of prediction,” said Dr. Chen.

The researchers are now working with Siemens Healthineers to integrate models from both studies into Siemens 0.55-tesla scanners so that scientists at other imaging research centers may begin using them, too. “We’ve already got some inquiries,” said Dr. Feng. “The goal is to have a very low field scanner to monitor and identify changes.”

Related Stories

Jingjia Chen, postdoctoral fellow who investigates longitudinal imaging and imaging in the presence of motion, talks about using the past in the present, improving body MRI, and taking better pictures.

Li Feng, developer of fast MRI techniques, talks about going beyond speed, his path to academia, and the rewards of persistence.