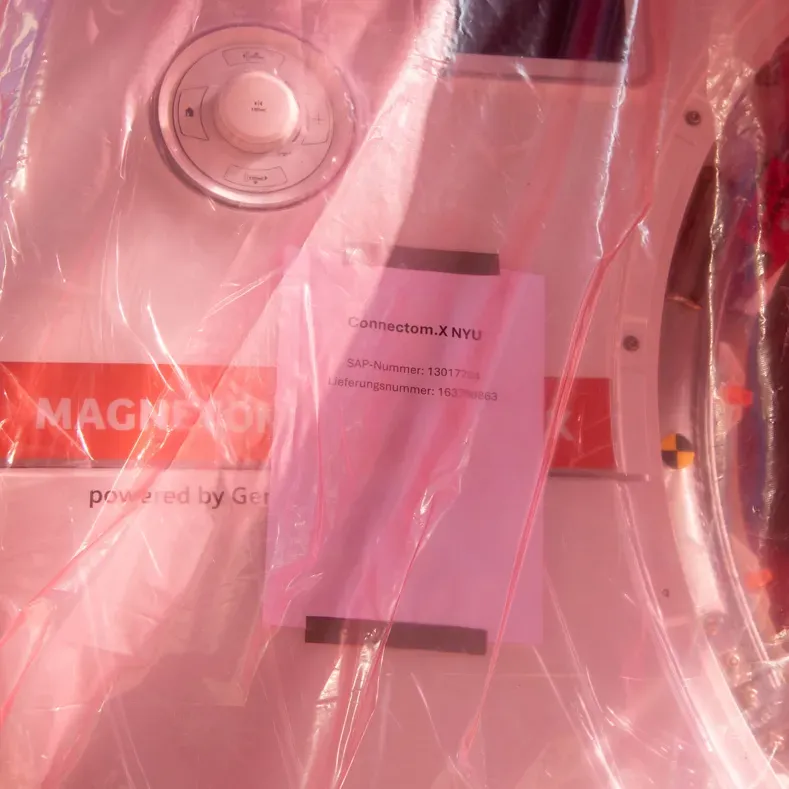

In November, NYU Langone Health installed a Siemens Magnetom Connectom.X scanner—a unique research MRI system able to noninvasively probe the living human brain down to the micrometer. The machine is only the second such unit in the world. Connectom.X brings to NYU Langone, New York City, and the broader region state-of-the art capabilities for MRI research on the most complex and perhaps the most mysterious human organ.

“The Connectom.X scanner is a major technological advance that will facilitate a leap in our understanding of the human brain and enable us to uncover what was previously invisible in vivo,” said Yvonne Lui, MD, professor and vice chair for research in the department of radiology at NYU Langone, which operates the Bernard and Irene Schwartz Center for Biomedical Imaging and the Center for Advanced Imaging Innovation and Research.

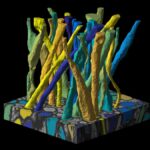

While clinical MRI scanners picture the body’s internal structures at the scale of millimeters, Connectom.X is a research-only, head-only system capable of probing the far smaller scale of microns through diffusion imaging.

Diffusion imaging uses magnetic resonance to sense the random motion of water molecules as they encounter cellular structures. Scientists can process this data to estimate nerve bundle orientations and generate tractograms or combine it with biophysical models to infer cellular properties such as axonal diameters, myelin thickness, cell density, and cell membrane permeability.

“This level of microstructural detail lies well beyond the reach of a clinical scanner,” said Els Fieremans, PhD, associate professor of radiology at NYU Grossman School of Medicine and principal investigator on a National Institutes of Health award that has supported NYU Langone’s acquisition of the Connectom.X system. “It really allows you to look at brain microstructure in all its detail.”

Dmitry Novikov, PhD, associate professor of radiology at NYU Grossman School of Medicine, added: “We’ve developed so much understanding of brain microstructure by building tissue models of diffusion, and finally we have a machine that will enable to us to see experimentally these effects that are either very difficult or impossible to see on a clinical scanner.”

“Looking” and “seeing” with diffusion means obtaining metrics rather than viewing the kinds of pictures produced by anatomical imaging. Drs. Fieremans and Novikov have been working together to push MRI past its millimeter-scale image resolution toward the realm of micrometer-scale diffusion measurements since the late 2000s. Through a systematic research program, they and colleagues have formulated new biophysics theories, conducted rigorous validation studies, and developed innovative technical tools to demonstrate that diffusion MRI signal can reveal accurate information about important physical and biological properties of tissue.

Telegraphing the potential of noninvasive access to such information, researchers sometimes use phrases like “virtual histology” or “in vivo microscope.”

What Makes a Connectome

Since MRI’s invention in the 1970s, researchers and engineers have pursued ever stronger magnets for more detailed images, but in order to achieve unprecedented diffusion sensitivity Connectom.X developers had to focus on a different attribute: gradients.

Magnetic field gradients are intentional variations in field strength along a chosen direction. These variations enable the MRI signal to be spatially encoded, serving a key role in the acquisition and reconstruction of anatomical images. But apart from determining signal location, gradients are central to diffusion.

“Stronger, faster gradients allow you to focus on the spread of the diffusion packet over smaller distances”—explained Dr. Novikov—“and therefore, to be sensitive to shorter length scales, a thousand times below the image resolution.”

The magnetic field gradient’s top strength and the speed with which it can be reached—known as maximum amplitude and slew rate, respectively—determine the granularity of spatial encoding, the rate of signal acquisition, and the amount of gathered signal relative to noise. Connectom.X can reach a gradient amplitude of 500 millitesla per meter and slew rate of 600 tesla per meter per second, roughly six-to-twelve times the amplitude and three-to-four times the slew rate of a clinical MRI system.

These specifications approach both technical and physiological limits. Rapidly switching fields can shake and heat the hardware and generate action potentials that excite nerves near the body’s surface. Connectom.X developers have used the latest advances in gradient design, innovative cooling techniques, computer simulations and volunteer safety studies to achieve the strongest gradients available in a research system to date.

The sensitivity the new instrument brings to human research allows inferences about such characteristics as diameters of nerve fibers and variations in thickness along axons. “You can really detect distinctive axonal features in white matter,” said Dr. Fieremans. “These are things that before you could only do in animal models. Now we can go from mice to humans and do it at multiple scales.”

From Connectomics to Microstructure

NYU Langone’s Connectom.X is the second such machine. The first unit was installed in 2023 at Massachusetts General Hospital, where Susie Huang, MD, PhD, associate professor at Harvard Medical School and associate director of the Athinoula A. Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging had led a multidisciplinary and multi-institutional team of scientists and engineers, in partnership with Siemens Healthineers, in an NIH-supported effort to develop the scanner.

Known also by its development name, Connectome 2.0, the system now branded Connectom.X is a second-generation instrument whose lineage traces back at least to 2009, when the NIH launched an initiative called the Human Connectome Project or HCP.

Inspired by the Human Genome Project, HCP sought to leverage the then-emergent field of connectomics to “map the circuitry of the healthy adult human brain” and create downstream benefits for science and health. To this end, an academic research consortium led by researchers at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard University in collaboration with the University of California at Los Angeles and later the University of Southern California undertook the development of Connectome 1.0.

In the late 2010s, a wide-ranging set of research programs aimed at deepening our understanding of the brain called the BRAIN Initiative supported the development of next-generation brain imaging tools and the evolution toward Connectome 2.0. The machine was to help supply a key link in the initiative’s objective to bridge scales and “generate circuit diagrams that vary in resolution from synapses to the whole brain.”

But concurrent research on diffusion MRI of tissue microstructure—including the field-defining program on biophysical modeling led by Drs. Fieremans and Novikov and colleagues—has in the meantime opened a new and compelling perspective on the potential of scanners originally aimed squarely at connectomics.

“Microstructure became a deeper subject,” said Dr. Novikov, and a perfect research application for the Connectom.X system. “In my opinion, it could well be called a microstructure scanner.”

Connecting Across Scales, Disciplines, and Institutions

Dr. Fieremans expressed hope that Connectom.X will draw scientists from many disciplines and research institutions in the region who are interested in using its unique capabilities. “You have a great concentration of knowledge and patients here, making it a great investment,” she said. “I think it’s a great choice by the NIH to put [the Connectom.X scanner] in a place like this.”

The instrument has already drawn interest from more than two dozen principal investigators at NYU Langone, Children’s Hospital in Philadelphia, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Columbia University, Johns Hopkins University, Massachusetts General Hospital, and Weill Cornell, for studies that range from imaging vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia to exploring the link between gene expression and brain connectivity to mapping tissue microstructure in Alzheimer’s disease to creating a three-dimensional micron-scale digital atlas of the human brain.

At the research frontier, demand for MRI machines with high-performance gradients has grown enough in the last few years to lead scanner manufacturers like Siemens, GE, and United Imaging to build such systems, though the number of models is still small. Over time, the bleeding-edge technologies tend to trickle down to a broader user base. For example, in 2023 Siemens introduced a whole-body MRI scanner called Cima.X with gradient specifications similar to those of Connectome 1.0—about half as strong as its successor, Connectom.X.

Dr. Novikov said devices like Connectom.X can help overcome a ‘chicken-and-egg problem’ in MRI microstructure mapping, where investment in high-gradient machines can be difficult to justify without the very biomarkers such machines are needed to develop.

“One has to break this vicious circle at some point,” said Dr. Novikov. With the accumulation of advances in biophysical modeling, animal studies, and research on earlier connectome scanners, “we hope that will lead to an explosion in this field.”

Dr. Huang, the scientist who led the NIH BRAIN Initiative-supported development of the scanner, echoed this sentiment. “I’m very excited that NYU Langone has gotten a Connectom.X because it shows that the technology is getting traction,” she said. “Putting this technology in the hands of more users will accelerate its adoption in both research and clinical translation.”

“This is a big milestone,” said Dr. Fieremans when asked to reflect on Connectom.X’s arrival, installation, and handover at NYU Langone. “It’s the moment we’ve been waiting for.”

The acquisition of research instrumentation reported in this story was supported by the National Institutes of Health Office of the Director under award number S10OD034309. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Related Stories

A fond look at the legacy and the final moments of an MRI scanner that played a special role in building NYU Langone's imaging research program.

Congratulations to Els Fieremans and Dmitry Novikov on being named among the 2024 senior fellows of the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine.

Scientists at NYU Langone Health show that MRI signal can detect axonal features long assumed to lie beyond the reach of magnetic resonance imaging.

Related Resources

Software for robust standard-model parameter estimation from diffusion MRI data.

Scripts for modeling the time-varying diffusion coefficient in biological tissue.

State-of-the-art denoising for diffusion and functional imaging applications.