On October 18 and 19, more than 220 people assembled at NYU Langone Health’s Manhattan campus for the third edition of the i2i Workshop, a conference dedicated to emerging frontiers in biomedical imaging and organized by the Center for Advanced Imaging Innovation and Research. The meeting—named after its tagline, “from innovation to implementation in imaging”—sought to explore connections between radiology and such disciplines as neuroscience, computer vision, materials science, nano engineering, and radio astronomy.

“I’m really inspired to see all the scientists who have gathered here,” said Yvonne Lui, MD, vice chair for research at NYU Langone’s radiology department, noting that “to be able to come together and try to better our world and try to move science forward” is inherently an act of hope and optimism.

“This is not a typical MRI workshop,” said Riccardo Lattanzi, PhD, professor of radiology and the meeting’s co-chair, on the morning of the conference’s first day, alluding to the unconventional selection of topics, which included: printing wireless sensors onto human skin; training AI to automatically segment cucumbers (or anything, really) based on text prompts; using Earth’s rotation to sharpen radio interferometry images of distant celestial bodies; detecting stroke with a combination of microwaves and machine learning; and probing cell development with nanodiamonds.

“We wanted to reflect together on what imaging really is and how it might change,” said Daniel Sodickson, MD, PhD, professor and chief of innovation in NYU Langone’s radiology department, principal investigator at the Center for Advanced Imaging Innovation and Research, and co-director of the Tech4Health Institute, who also co-chaired the conference. “In order to do that, we needed to connect different imaging modalities … different scales—the very small with the very large—and … take a look at our own biology and understand how our vision works.”

In the medical research community, “imaging” is primarily a byword for radiology’s long-dominant modalities: MRI, ultrasound, and several tomographic methods based on X-ray or positron emission. Research on such mature technologies requires a combination of deep expertise and fresh perspectives, and that’s what the co-chairs of the i2i Workshop sought to deliver by framing imaging among the many disciplines that study human vision or develop tools to extend it.

Urvashi Rau, PhD, scientist and image reconstruction expert at the National Radio Astronomy Observatory, who spoke at the i2i Workshop, said that “a diverse spread actually shows us what is common among these fields.”

“The way we sample partial information about an image is very similar to MRI, which means the reconstruction problem is pretty much identical in functional form,” said Dr. Rau. The big questions of how to see further and more accurately can boil down to the same physical, mathematical, or algorithmic principles. “All these fields have arrived at almost a common problem from different angles, which means each field has explored some angle in much more depth than others, so there’s a lot to share.”

Not all interdisciplinary connections are alike. Workshop speakers hailed from domains of inquiry linked to medical imaging in fundamental, conceptual, contextual, and complementary ways.

Nanshu Lu, PhD, professor of engineering at the University of Texas at Austin, who investigates wearables, showcased sticker- and tattoo-like electronics. “Our body from head to toe is emitting so much rich information—electrically, mechanically, thermally, even optically,” said Dr. Lu in an interview on the meeting’s first day. Her team is developing “skin-soft, hair-thin” wearables complete with network connectivity and power supply. “Our goal is to digitize the body—understanding your brain, tracking your cardiovascular health, tracking your emotions, your body hydration, and so on.”

Radiology, whose tools reveal what’s under the skin only on a one-time basis, provides doctors with a kind of snapshot per each imaging exam. What happens between scans is left out, often only to be deduced or speculated about once new images are taken. Machine learning and sensor miniaturization are now allowing researchers to imagine filling the intervals between imaging sessions with complementary data. “If we can have these tattoos that can continuously … track all of those events and physiology signals, then we can provide context for this snapshot imaging information,” said Dr. Lu.

Another theme on display at the i2i Workshop was low-field MRI, which has recently garnered increasing interest as a potentially inexpensive and therefore accessible alternative to the conventional scanners that remain unavailable to most in the developing world. In a nod to this burgeoning area, the Center for Advanced Imaging Innovation and Research hosted a hackathon, concurrent with the i2i Workshop, aimed at building a low-field scanner in under a week.

“It’s important that a topic like this would be useful here,” said Andrew Webb, PhD, professor of radiology at Leiden University, who investigates low-field, sustainable, and accessible MRI, which were the subject of his lecture. “To get the maximum performance out of these systems we need to borrow techniques that come from other types of imaging. In fact, ultrasound and optical [imaging] have some really interesting concepts that I think we can use in low-field MR.”

Spotted at the poster boards, Dr. Webb said that the vision for low-field MR is a “really, really simple, and really, really inexpensive” open-source system that can be built, operated, and maintained in under-resourced environments. Two major challenges, he said, are certification by regulatory bodies and acceptance by clinicians. “We have to determine exactly the clinical cases where these systems can be very useful.”

Next to the wood-paneled auditorium where speakers gave talks, a sun-streaked breezeway hummed with an undulating murmur of conversation, which rose to a din during coffee breaks, lunch, the poster session, and the closing reception. As attendees milled about, a few shared what brought them to the i2i Workshop and what they considered the meeting’s highlights.

Akbar Alipour, PhD, assistant professor of biomedical engineering in radiology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, said he found the sessions on ultra-high-field and low-field MRI the most interesting, as each area holds unique advantages. Dr. Alipour, who had attended the previous edition of the i2i Workshop in 2018, “knew how important it is for our community … you are going to get to know different people from different fields, [and] talking with them is going to bring in new ideas for you.”

Sarah Morris, PhD, medical physics resident in NYU Langone’s radiation oncology department said that she attended the workshop partly because she had conducted MRI research during doctoral training. She is hoping to merge her interests in radiology and radiation oncology through work with an MR-Linear Accelerator (MR-Linac), a tool that combines high-resolution imaging and radiation capabilities. “The AI talks are always interesting to me,” said Dr. Morris, and “I really liked Susie Huang’s talk.” Dr. Huang, associate professor of radiology at Harvard Medical School and clinician-researcher at Massachusetts General Hospital, spoke about neuroimaging with the Connectome scanner and its powerful gradients.

For Roberto Souza, PhD, assistant professor of electrical and software engineering at the University of Calgary, who specializes in AI-based image reconstruction, “there was one talk this morning that really opened my eyes … a way to approach MRI recon from the perspective of the uncertainty of the reconstruction.” He was referring to a lecture given by Jon Tamir, PhD, assistant professor of electrical and computer engineering at UT Austin, devoted to estimating how close AI-reconstructions come to learned theoretical properties of optimal images (a sort of theorized ground truth). “That really stood out to me,” said Dr. Souza. He also appreciated the balance of i2i Workshop’s location, size, and topics. “I wanted to know the new developments in the field … I also came because it’s not a huge conference, so I can network more easily with more people.”

Kristen Zarcone, third-year graduate student at Case Western Reserve University, said that her advisor, William Grissom, PhD—who was among invited speakers at the 2018 edition of the i2i—“had really wonderful things to say about the conference, so encouraged us to submit our work.” Her research poster titled “Palpating Particles Using the Acoustic Radiation Force” won second place in the scientific poster contest. “It’s a new approach to magnetic particle imaging where we replaced the expensive, bulky part of the imaging technique with a portable ultrasound-driven version and the goal is to make the technology more accessible and portable,” explained Zarcone. “It’s at the very, very early stages.”

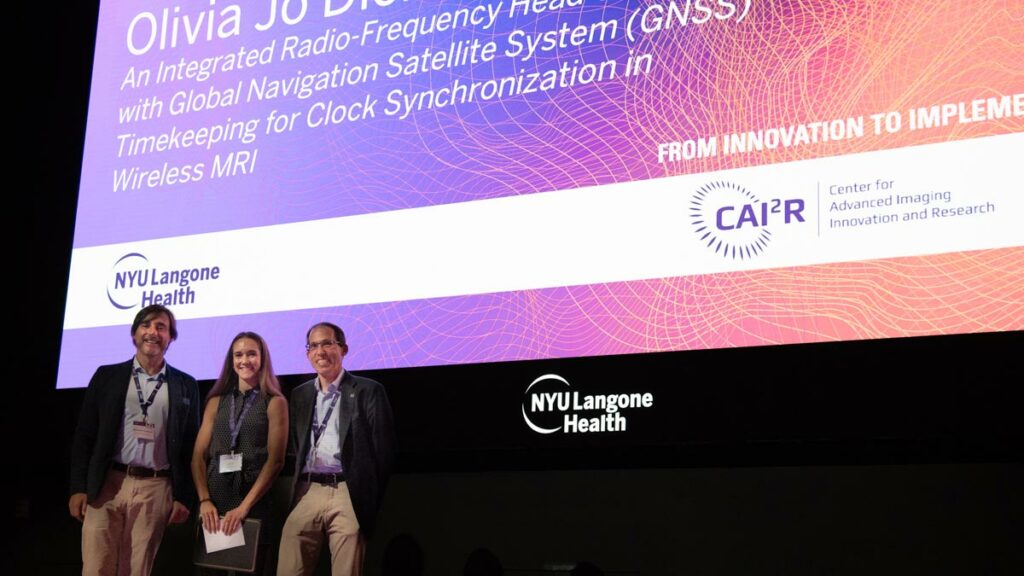

First prize went to Olivia Jo Dickinson, second-year graduate student at Duke University, for work titled “An Integrated Radio-Frequency Head Coil Array with Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) Timekeeping for Clock Synchonization in Wireless MRI.” Dickinson said that she especially appreciated Dr. Rau’s talk on radio astronomy. “I did astronomy research in undergrad, so I’ve always seen the connection between the two,” she said. “And now, as we work on wireless [RF coils] … using satellite time signals to synchronize clocks in the MR scanner, it’s a perfect example of literally bringing space information to medical imaging.”

As the evening of October 19 turned to night and the closing reception wound down, Drs. Lattanzi and Sodickson, the meeting’s co-chairs, lingered in the breezeway, amid emptying poster boards and receding traces of catering, until the final guest. A day earlier, Dr. Sodickson was asked about the decision to hold the i2i Workshop in its original, pre-pandemic format: as an in-person meeting without a live online component. “I think, just as we learned in the session this morning that there are multiple cues that the brain is interpreting in putting together a visual scene”—he said, referring to talks on the neuroscience of vision—“I think there are many subtle cues that go on between people when you’re trying to connect and innovate, and we felt like it was time to immerse ourselves together physically so that we could pick up all those cues as well.”

Related Story

How a moonshot effort to build an open-source MRI scanner from scratch in less than a week played out, and what it means for imaging research at large.