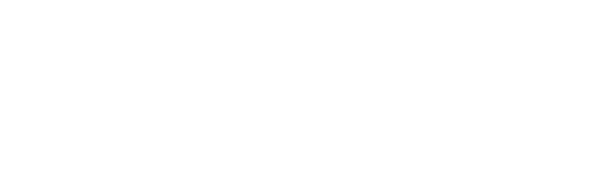

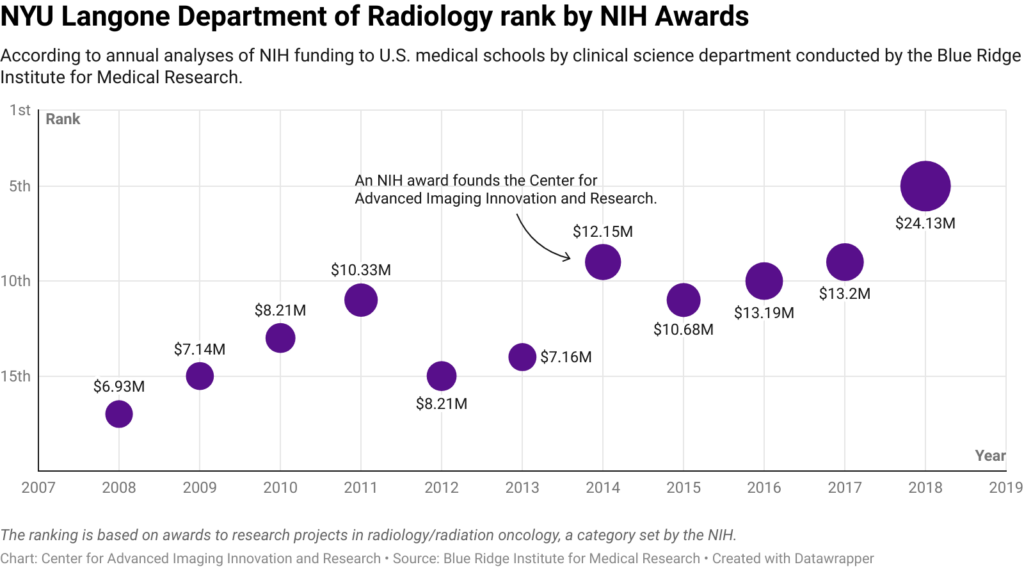

In 2018 the NIH awarded more than $24 million to NYU Grossman School of Medicine for imaging research. The total made NYU Langone’s radiology department the fifth largest recipient of NIH research funding among peer departments in the U.S., according to an analysis by the Blue Ridge Institute for Medical Research.

A look at the past decade shows a clear trend. In its 2008 analysis, Blue Ridge ranked our department 17th in the nation; in 2011, 11th; in 2014, ninth; and last year, fifth.

What accounts for this growth? We asked Daniel K. Sodickson, MD, PhD, vice chair for research at NYU Langone Health Department of Radiology, principal investigator the Center for Advanced Imaging Innovation and Research, and co-director at the Tech4Health Institute. Our conversation has been edited for clarity and concision.

Is there a particular formula behind the success of NYU Langone’s radiology department in securing federal funding for research?

Although I cannot say that there is a formula, I can speculate that there are contributing factors. Three in particular come to mind: culture, collaboration, and support.

What do you mean by culture?

We have made it a strong priority in hiring, communications, and day-to-day operations, that people respect each other and work together. We hire candidates we believe to be great people as well as promising scientists.

One time-honored way of rising in funding rankings is to buy grants—to recruit senior faculty who carry with them large awards. But we have explicitly chosen a different route.

We didn’t want to create laboratories led by big shots with their own gravitational fields who would pull resources away from our up-and-comers. Even though the right people can always inspire younger scientists, we wanted to grow our own thought leaders. So we did something that’s actually considered a bad idea in many cases. We hung on to many of our top-notch postdocs, and offered postdoctoral fellowships to a number of our graduate students who then worked their way up the ranks.

Why do you say this is often considered a bad idea?

A lot of established places tend to exile their own, sending them out into the world sort of by decree. That’s partly to ensure that students get the benefit of working in places other than where they cut their teeth, that they learn other environments and other scientific techniques, and that they aren’t seen as parochial when they’re being considered for promotion. In conversations with junior scientists interested in staying here, I’m always careful to tell them that they should consider their options for future positions broadly—I don’t want them to be constrained.

On the other hand, our institution has been changing so fast that in some ways the experience of these young people already has built-in diversity. We started as a much smaller, much more focused research group, and have since expanded and established leadership in numerous areas. The young faculty and the young scientists who have made their way through our team have had the opportunity to establish themselves as leaders in the state of the art relatively quickly.

The downside of our ‘hold on to talent’ approach is that it takes time for every young faculty member to find their way. It takes a lot of patience, advising, and support, and there’s no guarantee of success. With someone from outside, you have a past track record to go on, and everyone says that the best predictor of future accomplishment is past accomplishment.

In some sense you do have a record for people who have arisen through the lab—but it’s a record of a different kind.

That’s correct. With our trainees, we know who we’re getting, and we know that these are good people we can trust. There’s uncertainty in terms of funding record but also confidence in quality and conviction that we’re going to enjoy working together.

Can you unpack what you mean by “good people”?

When I say ‘good’ I mean possessed of a combination of scientific and interpersonal intelligence coupled with a combination of personal and collective ambition. If somebody doesn’t have any fire in their eyes then I don’t think that person fits well on this team because we are collectively quite ambitious. But anybody who is only interested in their own success doesn’t have much of a place here either. What we’re aiming for is a group of people who can collectively increase each other’s intelligence and productivity—you want the whole to be greater than the sum of the parts.

The other thing is, not every young investigator, or for that matter even every senior investigator, thrives equally in every environment, and so what we’ve tried to do is to create a highly-connected environment which maximizes the chances for young investigators to succeed. I’ve never been a fan of research enterprises which consist of well-defined discrete groups with clear boundaries and practical hurdles to intermixing. There’s a clarity to such a structure that allows people to operate without being interfered with. But I’ve always found it much more fun, quite frankly, when there are super-groups that interact freely.

This is the second factor you mentioned—collaboration.

Yes. From relatively early on I have characterized our radiology research division as a matrixed laboratory. At the beginning that was more of an aspirational term, but it has become increasingly definitional. I’ve studied models like Bell Labs, which went to great lengths to engineer the physical layout of their facilities so that people ran into each other on hallway paths or in common areas. While we have not, as of yet, been able to engineer our built environment with anything like that level of care, we have tried to do the same sort of thing intellectually.

How do you encourage that kind of free association across the lab?

I think—I hope—it’s the expectation that you will be talking to your peers. But we have also intentionally favored shared resources over individual resources.

For example?

For example, we tend not to offer eye-popping startup packages to new recruits. That is not by any means to say that we are stingy—we focus instead on what we believe will truly enable the success of up-and-coming scientists, including the common resources and the collaborative environment that you and I just discussed, along with active engagement by diverse mentors and other colleagues. A startup package is an amount of money, sometimes hundreds of thousands or even millions of dollars, for new faculty to spend in a certain amount of time. That money may support staff, ancillary hires, equipment, that sort of thing. For external recruits in particular, packages can certainly be helpful in a competitive landscape, and they may be necessary in some form to instill confidence, among those who do not yet know us, that we really will take care of our own. But I also feel as if many places will bring people in and say “Here’s your startup package, see you in five years.”

That kind of message automatically sets up a “make it on your own” mentality, and fosters competition for jealously guarded resources among people who are supposed to be working as a team. The current funding landscape already has set up the Principal Investigator as a C.E.O. far more than I would like. Every P.I. now has to focus not just on science and on managing people—the way it always was—but also on managing perception in social media, on public as well as academic promotion, on various metrics imposed both by research institutions and by funding organizations, on “how am I doing with my H factor?” and “do I have the right portfolio of grants?” This burgeoning list of job responsibilities constitutes one of the principal stressors for our team, and for any modern research team. Add too much competition to this mix, and you have the potential for real toxicity. So, if you start off with a startup package and a mandate to “go and succeed or you’re out of here,” I think it incentivizes balkanization.

What would you say to people skeptical of the approach you’re advocating?

I would say that there is actually some method to our madness. We do invest—and invest heavily—in shared resources. We want to give people everything they need, collectively. What we don’t want is to give one person what he needs and another person what she needs and, in the process, to create boundaries and duplication.

When I was hired by Dr. Grossman (then the Chair of Radiology, now the Dean and CEO of NYU Langone Health, and always a savvy manager of people), he told me, “I don’t believe in startup packages. Right now you don’t know what you need. You may think you know what you need, but you haven’t lived in our environment. So, come in, spend a few months getting the lay of the land, figure out what you need most, and then I’m going to give you more than you ask for.”

As I was considering the offer, just about every person that I ran it by told me I would have to be crazy to take it. Conventional wisdom held that after an initial honeymoon period you lose all leverage for negotiation, so you’d better get concrete guarantees of support up front. Certainly, such an approach is the safest approach to human transactions in general (safer, anyway, than unfounded blind trust). But I found myself believing Dr. Grossman. I felt that I understood his vision for the department and his reasons for recruiting me, and I went for it. After joining NYU, I looked around, assessed things, and went back to Bob to tell him that we needed a world-class RF lab and a core team to run it, and that I had an eye on a group of faculty in related areas whom I wanted to hire. “Here’s how much that’s going to cost,” I said. Bob’s reply was, “Okay, that makes perfect sense to me, but I do have a problem. I don’t think you’re being ambitious enough. Can you move on your recruits faster?”

That was the sort of framework that was set up for me when I first came to NYU. And that gets us to the third category of contributors to our success, which is institutional support.

You said you want to give everyone what they need collectively.

We’ve tried to centralize particularly valuable common resources so that people don’t need to hire all their own experts and buy all their own instrumentation. Our RF lab is a classic example. So is our new radiochemistry lab, and we’re hoping that our computational resources will serve in a similar way.

Another important thing is that our radiology department funds a significant portion of our research. In many top research centers scientists are responsible for 100 percent of their expenses. Basically, you eat what you kill. And although we aspire to covering an ever greater proportion of our research costs with grants, that’s not a way to grow a program—that is, at best, a way to maintain a program once you have one. If you want to grow, you have to invest in new people and give them the chance to succeed or fail. And you also have to invest in crazy ideas that don’t have a good chance of working.

Here I have had the great advantage of a boss and a partner—Dr. Michael Recht—who believes in just that sort of investment. Dr. Recht, who took over from Dr. Grossman as Chair of Radiology back in 2009, has led a remarkable decade of growth in our department. Our clinical volume has grown from 345,000 imaging exams per year in 2009 to over 2 million per year in 2019. Michael has a keen eye for efficiency, and extraordinary business acumen, and many in his position might have been content to revel in the resulting financial success. But Michael also has an uncompromising commitment to transformation. With support from Dr. Grossman, Dr. Bar-Sagi (Vice Dean for Science) and others in NYU Langone leadership, Michael has reinvested clinical revenues back into various key drivers of our department’s reputation and culture, including research. At present, 50% of our annual research budget is derived from clinical revenues. If you did a survey of Radiology departments around the country and the world, I think you would find this to be a remarkably vigorous investment. This is what allows us to grow strategically, and to provide our research team what it needs, collectively, to innovate.

To have significant impact, you need both disruptive innovation and iterative development. How can we foster an optimal balance between the two?

I enthusiastically encourage people to keep their eye on the larger story arcs associated with their research, and to focus on unanswered questions and unsolved problems which can be the drivers of disruptive innovation—not just on pursuing the grant metrics, which tend to skew towards iterative development. And that’s another thing that’s important to say here. In our department, we care about our grant standing not as an end in itself but as an indicator of our impact. And I really think that in order to have maximal impact, you need a combination of grant success with freethinking and protected time. One needs, in Virginia Woolf’s words, a room of one’s own.

That room is both increasingly important and difficult to find.

The problem with the current funding landscape is that, just by the nature of peer review, ideas that have a high likelihood of working are funded far more often than ideas that are high-risk. And once such ideas are funded, the funding carries with it a host of administrative responsibilities which can leave little time for reflection. I think the best way to lay the path for innovation is to allow people to think freely without constantly worrying about the bottom line. But not so freely that they lose sight of the world around them. The Idea Factory: Bell Labs and the Great Age of American Innovation, a book I find particularly inspiring, lays out the power of giving people the freedom to explore while constantly exposing them to unsolved problems and unmet needs in a practical area of endeavor. For Bell Labs it was communications; For us it is biomedicine. And in order to do that you have to cover people’s time while they’re thinking. We have the good fortune, both in terms of our clinical revenues and in terms of our overall institutional support and philosophy, to have been able to invest above and beyond the grant dollars that flow in. So, we’ve invested in equipment, we’ve invested in computation, and we’ve invested in good people as they’ve ramped up their research programs and found their own particular directions within our matrixed laboratory.

If my hypothesis is correct, all of this is what enabled our investigators to come up with the new ideas that were the seeds of some of our latest grants. Culture, collaboration, and institutional support really have been the drivers of our decade of growth. I look forward to seeing what we can do together in the decade to come!

Related Story

Since 2014, the Center for Advanced Imaging Innovation and Research has been in the lead of technological shifts in magnetic resonance imaging. An award from the National Institutes of Health is extending the center’s mandate for a third five-year term.